Talking Resilience, Musical Heroes, and Weird Scene Bullshit with Buick Audra of Friendship Commanders

BILL- The Steve Albini Mixes- is out today.

Buick Audra and her heavy melodic duo Friendship Commanders made their way into my life a few months ago when someone shared a Rock And Roll Fables post about them on Facebook. My interest was immediately piqued as I read that they were re-releasing a record, this time sharing Steve Albini’s original mixes with the world, and that working with Albini had drawn some “weird” and “unfortunate” reactions from people in their lives. It sounded like some bullshit misogyny and a good story to me, so I wanted to see if Buick would sit down and talk with me about it. I was met with a friendly affirmative and this interview ended up being the first one that I’ve recorded via audio for High-Pass Filter. I knew that I’d want to be able to respond in the moment and not rely on emailed answers this time around.

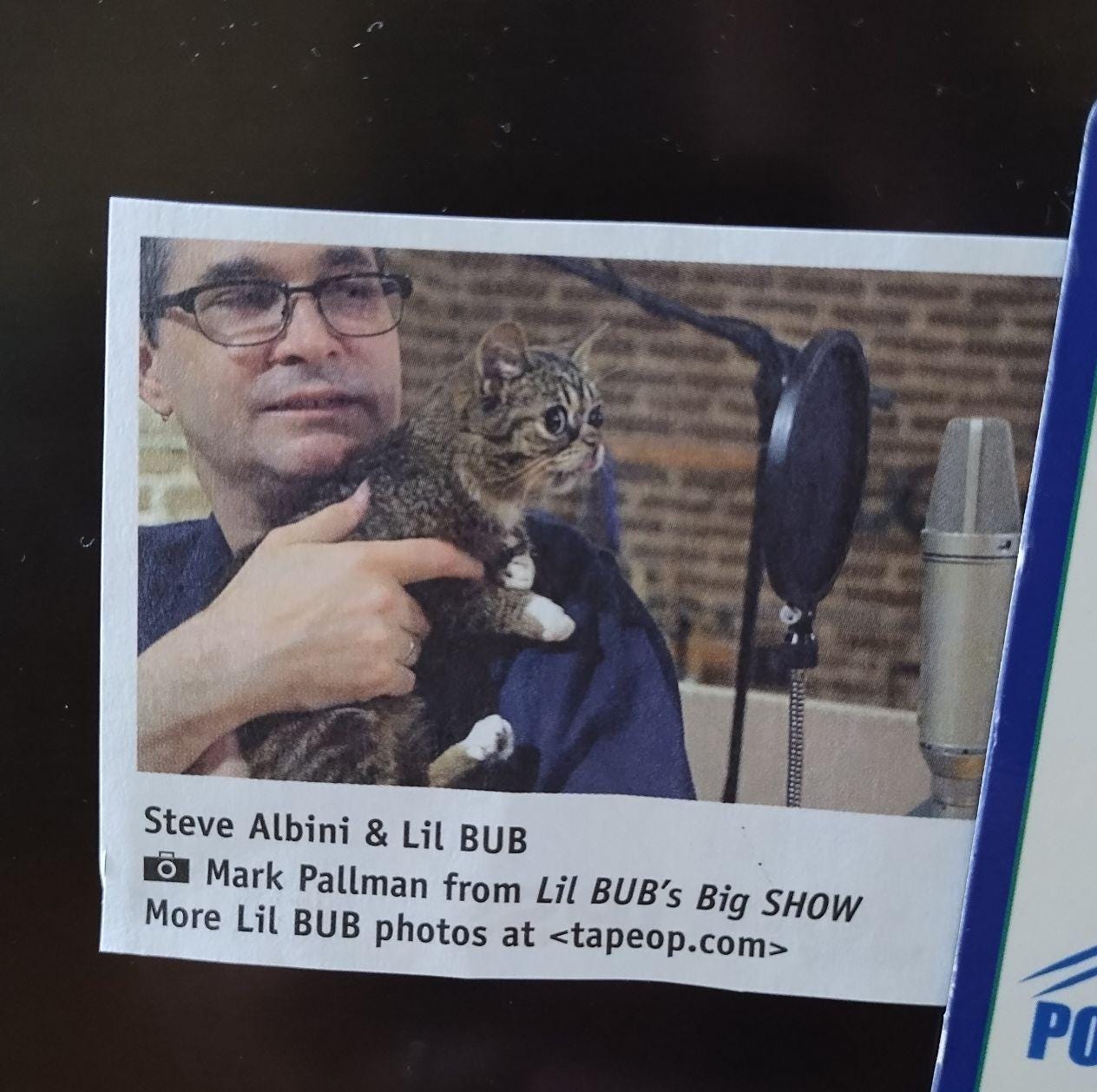

Buick Audra is a Grammy Award-winning songwriter, musician, and writer originally from Miami who spent much of her youth in Massachusetts, primarily in Belmont and then Dorchester while she attended MassArt. Buick now lives and works in Nashville. She has released a number of solo records, two books, and her band Friendship Commanders— with partner Jerry Roe on drums and sometimes bass— has just today re-released their second record, BILL. This time around we get to hear the original Steve Albini mixes. Albini, the illustrious musician, engineer, unironic poker champion and absolute force of nature, passed away suddenly following a heart attack on May 7th and would have turned 62 years old today. It feels right to learn he was an undercover water sign the whole time and it’s still unreal to me that we’re living in a timeline where Donald Trump is alive and Steve Albini isn’t.

I said what I said. Unfriend me, Jack Black.

The following conversation has been edited for length (I swear!) and clarity but much care was taken to maintain the integrity of all that was said. A few exchanges took place via follow-up email after our initial call and I’ve left any minor formatting differences alone.

Buick was a joy to talk to and I’m grateful that she was willing to be so candid and vulnerable with me.

HPF: First off, you grew up and have lived in a few very different places. Do you find that your roots in Miami and New England especially end up showing through the work that you’re doing now that you’re in Nashville? Do you find that there’s anything different about your approach?

BA: I'm definitely an outsider everywhere I live, which is partially a feeling and partially a truth. MASS, the last album that Friendship Commanders released, which only just came out in September, is about my time in Massachusetts and how bizarre I found that time in hindsight. Not necessarily when I was there, but when I looked back after my friend Marc Orleans [of Sunburned Hand of the Man] took his own life in 2020. I was like, that time was strange, and I wrote that album about that. So I was an outsider there too but a different kind of outsider than I am here. And I'm sort of just used to being an outsider. Although in Nashville there's quite a lot of community here that's not from here. My partner is actually from here which is kind of rare. But a lot of people have moved here, like myself, to make music and it used to be that we moved here to make music someplace we could afford living. I actually moved here from Brooklyn where I was paying hundreds and hundreds of dollars a month to have a rehearsal space that I shared with like five other bands. And you know, when I moved to Nashville by myself, I just thought like, I need to be somewhere where I can like record in my own space once in a while if I want to, and not just have everything be this enormous effort and expense. Now Nashville has moved away from being affordable at all, but it was when I [moved here]. There are a lot of people here making work that are from wherever, all over Hell's Half Acre. But I do think that I am less adaptable than some. I definitely am an east coast energy you know, that sort of… as I said, I'm originally from Miami. I have a very straightforward presentation of my ideas.

HPF: Ha, yeah I think that was kind of what I was getting at…

BA: I’m very bold. [laughs]

HPF: That’s definitely clear from the music [of yours] that I’ve listened to so far. And there is a directness, I think, with a lot of musicians here in New England anyway. It is interesting. I feel like anybody who seems to be leaving New England for musical purposes, from my experience, seems to be going to Brooklyn, Nashville, LA, and for some reason Colorado. I’m not sure what’s going on in Colorado.

BA: Oh interesting.

HPF: Yeah I’ve had so many people— I mean maybe it’s a coincidence and they’re not moving just for musical reasons but it seems like there’s some sort of scene up there that is very foreign to me. I’ve never been through.

BA: I like playing in Denver, I’ll say that. And there’s that town that The Descendants live in… I can’t think of what it’s called right at this second [Buick texted later to say it was Fort Collins], that’s about an hour north of Denver that’s a college town. But Bill Stevenson opened his studio up there y’know years ago, the Blasting Room, it’s called. Which I think is where The Descendants stuff is made now most of the time.

HPF: Interesting, I didn’t know about that.

BA: But yeah, I have lived in LA, for like ten seconds, a long time ago. I lived in Brooklyn for four years and now I live here, and I fit here the least by any measure. But at this point— it’s sort of it’s funny because I’m writing a lot of music about not fitting anywhere right now, so it’s funny to be having this conversation— but at this point I feel pretty committed to just bringing myself to wherever I am, as opposed to necessarily fitting there because I’m sort of worn out on worrying about that. [laughs]

HPF: Right, absolutely. Yeah you’re the artist and you’ve got your music. You’ve got to bring yourself into it.

BA: Yeah. And there are things to love about Nashville for sure. There are things to love here. One of them is touring from here, because I live in the middle of the country and let me tell you, as a child from Miami, we saw whoever could make it all the hell the way down there, you know what I mean? Because we were in the middle of the ocean.

HPF: I’ve had friends in Maine say the same thing.

BA: Yes! People in Alaska? Like they’re going to whatever show is coming to Alaska; it doesn’t even matter how much they like that music. So being in the middle, so to speak, is really good for touring and just for accessibility in general. There are things to love. And you know, there are some incredible recording studios here and some incredible musicians and being a heavy musician, particularly being a woman in heavy music, sort of stands out some. But that’s okay, you know. There are worse things than standing out some. [laughs]

HPF: That’s always a double edged sword. I think about that a lot and I’m sure it’s gonna start making its way more and more into my writing but just how there’s sort of this fine line between representation and being treated as a novelty. Where, I certainly want people to see me as a, y’know “Female Musician” doing what I’m doing but I don’t want that to be the reason that people want to listen to my music in the first place.

BA: Yeah.

[I ramble on about this for a bit here, as I often do.]

HPF: You’ve described working with Steve Albini as “changing your life” and I was curious if you could tell me a little bit about how his work and music made their way into your life. How did you become a follower or fan— or however you’d describe yourself— of Steve Albini and then how did you end up working with him?

BA: So, I’m a Shellac person. For sure.

HPF: Me too! Me too.

BA: Oh good. A fellow kindred. Yeah Shellac was the first work I ever heard of Steve’s, or that I was aware of knowing was Steve’s. And it’s funny because now, y’know, I meet so many people who think of Steve as a recording engineer and that’s true. He was, but I think of Steve as one of the fucking raddest musicians that I coexisted with in my lifetime and the first time that I heard Shellac I was like… I understood it on a cellular level. It wasn’t even that I liked it; it like fucking… all the way into the marrow of my bones. I was like finally, y’know, this exists. I just wanted it in my bloodstream, forever from that day. And I am not a person for whom nostalgia functions at all as it relates to music. I grew up with so many guys and played music with so many guys who have that thing where the music they listened to when they were twenty-two still makes them feel a certain way. I don’t have that. The music either still is good to me or is not, and a lot of it is not. And Shellac is still some of the baddest shit I’ve ever heard in my life. And the new record, of course, is astonishing. So I came into Steve through Shellac and then of course became aware of him as a collaborator with so many other artists, some of whom were really important to me and some of whom were not. But he just is a contributor to culture in that way. And the records that he did make that I loved, I loved hard and he certainly was my favorite recording engineer for years and years and years and years. And y’know, there was a lot of mythos around Steve as I’m sure you know. There still is. And for a while there in the middle I was like, I guess I’ll just never work with Steve because I like him so much and I love his music so much that I guess I just won’t worry about it. And people are like, “Oh don’t work with people you admire” or whatever. I’ve worked with everybody I admire, just about. I started where I admired. I mean the first record I ever made was with J. Robbins [of Jawbox] at Inner Ear [studio in Arlington, Virginia].

HPF: Oh shit, that’s awesome.

BA: There’s a lot to admire there, y’know? And Ian MacKaye helped me put it out. I’m not afraid of that per se but Steve was in kind of a different bracket and I just thought… also Rainy, to be honest, I had been abused by a long term collaborator, a recording engineer around my voice and my sense of pitch and it really had done an incredible sort of slow burn number on myself that I still find pieces of, like shrapnel in my system. And it’s years that I haven’t known this person. So, I think there for a while I was like I’m already injured and I can’t afford… I don’t have the type of resilience that it might require if I were to work with Steve and he were a dick. It would be devastating on a level that I don’t have the capacity to metabolize at this time, y’know? And so I just never worried about it. I never considered it anything that I needed to do and I just loved his work and I loved Shellac and that was the end of it. He was over there and I was over here. And then in 2017, Friendship Commanders were scheduled to make our second record with another engineer, another really cool musician and person in the world and at the last minute that plan fell apart on the end of the engineer and we were suddenly without a plan for making the record. We had a manager at the time and we were on the phone with him kind of panicking, and he said, “Well, make a list of people that you would consider working with and we’ll start reaching out.” We started spitballing some names and he kind of cut to the chase and said, “Well who’s the dream?” And I said, without even breathing, Steve Albini. And he said, “Has anybody called Steve Albini?” And I thought, oh no… y’know? So we did reach out to Steve and he checked us out, and he said yes.

HPF: Hell yes.

BA: And then it was about letting go of whoever he was in the space. I remember my work for the months leading up to that recording were about being as prepared as I could, because we were tracking to tape, which is— as you know as a musician— like, the stakes are much much higher and the margin for error has to be considerably lower and you really have to have your shit together. And also, there’s a tight schedule. It was a big record and it was an expense. It’s an expense to travel out of town and make a record, especially with somebody who has a lot of shit going on. So I prepared myself for months musically and psychologically and I got to this place where I was like, regardless of who this man is, he’s the best at what he does on a technical level and you’re also very good. So just be good and don’t attach yourself to how he responds. Just be an adult in the space. Be a peer.

HPF: What you were saying about being afraid that you were gonna find out that he’s a dick or something, that resonates with me so much because I’ve thought in the past about who would I want to record with, but who do I think I would actually play my best working with, and y’know, my fear… I mean now unfortunately I’ve lost the chance to ever actually work with Steve Albini, but I was thinking about how I always felt like I would be so weird around him for the first few days unless I went through this huge preparatory process. Like I’m not going to get the best out of myself, through no fault of his. I don't know if intimidated is the right word, but the idea put me in this sort of weird space.

BA: Yeah, I don't know if I was intimidated either, but I was definitely self-protective and rightly so. I was not willing to take on more damage from some fucking guy, frankly. Which this other guy was, the guy that injured me, you know.

HPF: I'd seen recently— I think it was on an Instagram video— you'd said something about typically always recording your own vocals. Was that kind of the impetus behind this? Because of what you were put through?

BA: Yeah, so after I worked with the person that I did for as long as I did, it was either like quit music or find a different way to do it, honestly. So I got very good at engineering myself. And I mean I've engineered a bunch of other stuff for people too, but it was really important for me to have control and not have to be in the room with some dick who had something to prove to himself or anybody else. And also, these people who give people shit about vocals can't sing, and I just want to say that on the record. Please print that. They're the worst singers you've ever heard. He's done his own project too, and he's the worst singer in town.

HPF: Well from what I've been listening to, I mean you have such a powerful voice. I would never think of you as somebody who's taking shitty vocal feedback from like you said, some fucking guy.

BA: Yeah, exactly. Thank you for saying that. My voice has actually gotten bigger in the wake of working with [that other guy]. He really wanted me to play myself down. He didn't like the power in my voice and the whole fucking thing. I had issues around trusting other people or even being interested in wanting them to record my vocals, so I got good at doing it, and then when we committed to making an album with Steve, you know, that's like a whole other ball of wax. Because it isn't this thing of like, “Oh I'll just take the session home in the hard drive and track myself,” right? We're literally making an analog record. So I had psychologically sort of moved into that space where I was like, okay, not only am I going to let someone record my vocals for the first time in years, it's going to be Steve Albini today. And he's doing it in this great room…

HPF: Go big or go home.

BA: Yeah, exactly. So we did the basic tracks for the record. We're just two people, so drums and guitar, whatever, and then it was time to start vocals. And I went up into the lofted control room where he spent most of the record, just by myself with him, and I said, “Listen, we have to square off about vocals. Like I don't let other people record me.” And he had been fussing around with something, and he turned around and sat down to listen. I want to say too, that up to this point— this is like day, whatever it is, three or four or something— I had already really eased into working with him. I was already very comfortable with him. Vocals were a different frontier but I trusted him, and I said… you know, I just thought I'd be brave, and say, “I have experienced abuse, and this is what it looked like, and this is what I'm willing to take, and this is what I'm not willing to take.” I explained exactly what had happened and he was very quiet, and he kind of looked down and nodded his head, and he said, “Sounds like a dick,” and I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “I've heard of guys like this. I don't know why they work in music. I don't know why they work with other people. I could never understand why this is a thing.” Then I was kind of quiet for a while and he said, “Well, I invite you to leave it here. Leave your trauma and your injury here in the studio. You don't need to carry it anymore.” And I was like, okay. And I walked downstairs and I cut that record in six hours. Steve was just delightful. We laughed, you know, and he gave me a lot of feedback. I came back up after the first couple of passes, and he said, “Well, turns out you're a great singer.”

HPF: This is so heartening to hear all this about him.

BA: Yeah, right? He heard me like a normal person. He was like, “You're a powerful singer; this will be fine. Let's just roll,” you know. He would bring me tea. I have these memories of Steve walking down the Studio B stairs bringing me tea so I wouldn't have to leave the vocal station. He just wanted to keep it rolling. Once we were on a roll, he wanted me to stay warm and keep going, and it was so fun. It was super, super fun. I hadn't had fun tracking vocals with another person maybe ever, or it had been a long, long time, and it was delightful, and I keep it with me. I did leave that trauma there, and my voice has, like, tripled in size since those sessions. If you listen to MASS, you'll see, my voice went a different way, you know. It really reminded me that I love to sing and that I do sing well, and that other people's abusive tendencies have nothing to do with me. Someone pointed it out to me recently, because people love to make Steve the hero of my life— because that's what we do with voices: women have no agency— and someone said, “Well, you did that. You were great. You showed up as yourself.”

HPF: I mean, it sounds like you gave him the container to put the feedback in. You gave him the container to put the advice in, so you let him change things for you.

BA: Yeah, I was responsible with myself. It's like, you know… I'm an abuse survivor on a physical level, too, and when I go see a healthcare practitioner, I tell them that. I say, “I'm an abuse survivor. This is what I need.” And so I did the same thing with Steve. And he was a grown adult who took the note, and we had an awesome time. It really did change my life because I think having that experience with one person— now I track my own vocals because I'm good at doing it, and I love doing it, and I get to explore stuff that I wouldn't in front of someone else— but like, I could no problem now, because I've already crossed that bridge, you know?

HPF: Yeah. The “process” pieces are so important to the ultimate product, and how you feel about it, and how you feel about yourself when recording. Actually, speaking of process, I was curious: How did you end up mixing BILL with someone else the first time around? Were you originally supposed to have Steve mix the record the first time, or…?

BA: So Steve mixed it during those sessions; we left with a finished album. He mixed it first and these are the original mixes that we're releasing right now.

HPF: Ahh okay. I had it reversed. I was thinking that the other person mixed it, and then you went and had Steve mix it or something.

BA: No, no. Steve mixed it. We finished the record with Steve, we left, and as we were driving back to Nashville listening to the mixes, Jerry, who is the other person in my band, was like, “I don't think I can live with these mixes.” And he mixed the record. It's not an outside person.

HPF: Okay, I missed that piece! I missed that Jerry’s was the other mix.

BA: Yes, yes. So Jerry mixed it and you know, he did a great job. They're beautiful mixes. They're just different than Steve's mixes. And I was really taken with Steve's mixes, but I— you know, being in a band is being in a band. Sometimes you come to the middle where you would never normally, you know, whatever. But he felt very strongly that my voice wasn't sort of forward enough, and there were certain things about the drum mixes that he… drummers can be… [they] have their own ideas about what's happening. [laughs]

HPF: [laughing] Yeahhh, drums are my first instrument... In my current band I am the bassist, but my partner who is our drummer was much less experienced when he started in this band. I told him, I said straight up, “I am going to try not to Dave Grohl this whole situation, but I am going to have a lot of strong feelings about drums.” And because we work together so well, it's really worked to our advantage, because he wants to listen to my feedback, and he wants to work with me and play with me. So now, once I got comfortable with that, and he got comfortable with that, it's just been this sort of constructive process. But yeah, it's hard when you are the drummer to hear… [laughs] to hear drums differently from… I mean, I think it's true of any musician, but… I get it. [laughs]

BA: And Steve is such a different animal than like everyone else that ever lived. He just has such a specific set of tonalities and tendencies, I think, the way that he heard music was so... I'm still learning how to speak about Steve in the past tense. It makes my eyes water.

HPF: Yeah. Trust me… when I heard that he’d passed, I think I just had my mouth gaping open for two days.

BA: I literally fell to the ground. I collapsed on the ground when I saw that. I couldn't... I actually thought it was a hoax at first. I went to abject denial and then just spent two days on the floor. So I'm still metabolizing the change of tense. I'm not great. I still speak about him in the present tense sometimes, which is fine. I talk to him all the time.

HPF: He's still affecting all of us.

BA: Yeah, I love him. But… what the hell were we talking about?

HPF: Well, just the mixes and the process…

BA: Oh, the mixes. So Jerry remixed the record, and we released Jerry's mixes, and they were great. And then it was always the plan that we would release Steve's mixes. We'd just have two versions of the record out. But we toured on the original version of BILL up to the pandemic. It came out October of 2018 and we toured on it for a year and a half. And then we made an EP at the end of 2019 that we tracked here in Nashville, and then Kurt Ballou [of Converge] mixed it. It was our first collaboration with Ballou, whom we've now been working with for five straight years. We made MASS at GodCity in Salem—

HPF: In Salem, yeah.

BA: So, you know, we were like, oh, we're going to release this Hold On To Yourself EP. And in that time between releasing BILL and making Hold On To Yourself, like my writing had gotten quite a bit heavier, and we were just like… the sensibilities were changing. And then it was the pandemic. I mean, Hold On To Yourself came out April 3, 2020. How nice. We were supposed to tour on that all year. And then I just moved into the space of writing kind of like reactive, responsive music about the time we were living in. And, you know, life just rolled down the road. I wrote MASS after Marc killed himself in 2020 and blah, blah, blah. And it just stopped being a thing that was pending, like releasing Steve's mixes of BILL. And also, I mean, childishly, I just sort of thought Steve would live longer than all of us. He's been such a constant in the world and in my awareness since I was a kid that, I don't know, I just, it was irresponsible. But when he died, I said to Jerry, like, “We have to release these mixes.” Not to draw attention to ourselves necessarily, but because we're sitting on a record that Steve did. And everything that Steve contributed to should belong to everyone at this point. And Steve's mixes are different. They're super “guitar forward.” They're very “me forward.” He was very… he championed me a lot on the record, which I think you can hear sonically. And we released “Outlive You” as the only single because it was Steve's favorite. He loved that song.

HPF: I really did want to hear about these adverse reactions you were getting from people for having worked with him. One comment that really blew my mind was that somebody— another musician or a friend of yours?— had said that her boyfriend or husband was the one who “deserved to work with him?”

BA: Oh, yeah, we got a lot of that. Oh my god.

HPF: Tell me about this bullshit.

BA: It was wild, Rainy. I mean the day we announced that we were going up to Chicago to make socials, it was like an explosion of vitriol about Steve. People who had heard about someone who had worked with… everybody loves to trot out that Cloud Nothings record as if Steve like, murdered the whole fucking band, you know what I mean? Like it’s such a weird… I don't care! That's none of my business, you know? Whatever. There was just a lot of, “Well, some label head emailed us and we sent this band up to work with Steve and the record’s unusable. He's a nightmare,” you know. And I remember going out to lunch maybe that same day and we ran into a recording engineer. He was like, “Are you guys really working with Albini?” and we were like.. yeah, we were thrilled! You know? Like, my childhood dreams are coming true; I’m doing it! He was like, “He's an asshole,” and it was really interesting… mostly from men. And what I got from women was a lot of like, “Well, you know, Mikey's been in a band for twenty years and they've never worked with Steve—”

HPF: So saaaaaad!

BA: “—and I just feel like he's more deserving.” I mean it was like everybody who ever had worn like a thin mask of being a regular member of society suddenly ripped it off like a Scooby-Doo episode. And just showed like… envy, resentment, competitiveness, like it was bizarre. There were very few people who were able to be like, “Good for you. It's gonna be a great fit. He's gonna love you what you guys are doing.” Very few people could afford to say that for some reason; even long-term friends of mine and guys I had collaborated with. I remember calling someone the day we found out we were making a record with [Albini] and him being like, “Okay…” Y’know? Because he was his hero right now. So I had to accommodate the hurt feelings of just ridiculous people and it was really… I mean…

HPF: Here's some more emotional labor for you to do!

BA: Yeah! It was a drag. I'm not gonna lie to you. It was a fucking drag and it just went on and on through the release. It's hard for me anyway to stand with myself because I'm an abuse survivor, and because of the familial context. My mother is unkind to me and competitive with me about my music and so I think I have also attracted that brand of person to me throughout my life. I mean, I know I have but even people that I don't have that much intimacy with had a really hard time with us making a record with Steve and with putting it out. And and then another part of it was that people made the whole record about Steve. Press made it just that “Steve Albini had made a record,” you know? And then Nashville made it about “Jerry had made a record with Steve.” [laughs]

HPF: [sighing]

BA: And I was like, “I wrote this record,” you know? How are we talking about only the drummer make a record…

HPF: See now I'm glad that we're on video so you can see me rolling my eyes at that…Yeah, it really sounds like people acted like you had just gone to the top of the mountain with all the other pilgrims and Steve, you know, picked you with the claw machine. And it’s like, no: you were working with him.

BA: And then I remember there were a bunch of people who would say stuff like, “Oh well He'll work with anyone right?”

HPF: Oh, yeah. So you either get “He's choosing you in particular” or “He's working with you for some reason that you don't deserve.” It’s all your fault or you don't matter at all.

BA: It was wild. I mean, it's funny now we work with Ballou and to some extent I get some funny comments about Ballou, but he’s less of a cultural juggernaut. Steve, he's like a publicly traded identity and it's weird how Gen X— I mean they actually think that they own parts of his identity and have no problem telling you that. Just burdening you with whatever they think about him. And just so many men explaining who Steve is to me still I mean, but certainly back then. Like well, “Steve's a really important—” [laughs] I'm like, “Oh is he???”

HPF: [laughing] Tell me more!

BA: I dunno I how I got in there! I just opened some studio door and there he was!

HPF: You won it on a game show!

BA: Yeah, I know… I mean people explain who Ballou is to me too. And I'm like, yeah I’ve worked with him for five years. I see you've never met him, but still you're explaining him to me. Thank you for that, you know? So it's been a lot of that and when we decided to release Steve's mixes I felt it all come back up. I was like, oh god, I fucking remember what this was like, you know? I mean even when Steve died and I made posts about his passing I turned off all the comments because I was like… I just don't want to hear from Gen X men right now. Again.

HPF: Ugh, god. I know this feeling. [sighs]

BA: [laughing]

HPF: I have so much more to say. But before we part ways here, I do actually want to ask you some questions about the record itself. Right off the bat, the lyrics on BILL are intense. The opening track “Your Fear Is Showing” has a hand reaching out of a grave to try and pull you down but you’re like fuck that. Throughout the rest of the record, I’m finding places where you’re asking questions or saying, "I don’t know how this situation works, I’m not sure what to do," but also a lot of these declarations of not taking shit and of standing up for yourself. Is it safe to say that this whole album is an emotional emancipation? Do you think of it as a concept album?

BA: This is such a great set of observations - thank you for taking the time to check out the lyrics! I’m not a person who listens to my own work once it’s been released, so I hadn’t revisited the sentiments expressed on BILL in a while. When Albini died and I started to listen back, I was like, holy shit; I was really going through it on this album, kind of fighting for my life in a number of areas. This record was written in a season of loss and transition, primarily around friendship. I’d had some friendships with women end in ways that sent me reeling, and it caused me to dig around in the dirt of all my past friendships, examining where I’d missed things or not understood what was happening. Because I’m an abuse survivor, prior to this excavation, I believed that all relationship failures were my fault, that I was the defective factor. And on BILL, I’m saying, here’s what my belief has been for years and years, but if I let that be true, I can’t keep living, so I have to lift this proverbial car off of my own chest. Save my own life. There’s a lot of push and pull on this record—with myself, with my own fear of being fucked up beyond lovability. It’s an emotional emancipation for sure. Now I think of this album as the grief record. But all the facets of grief, not just sadness. It embodies anger, disbelief, clarity, etc. So, in a sense, yes – it IS a concept record, but I’m not sure I understood that at the time.

HPF: I couldn’t help but think about how you first released BILL two years prior to COVID, and now here it is being released four years after the pandemic started. Do you feel that your relationship with this piece of work or your feelings about it have changed since the first go-around? I'm just thinking about how everything seems to have been altered on either end of the pandemic looking glass.

BA: Oh, for sure. I couldn’t write this record today if my life depended on it. I’m a completely different person now. Even musically, this is like, so far away from me today. I’m not sure the pandemic is the sole factor, but it’s certainly one of them. Another factor is the suicide of my friend Marc Orleans in the summer of 2020 (about which I wrote FAIL on the MASS album by FC). Marc’s death ripped me from the frame in a way that changed the way I see things, especially friendships. It gave way to clarity around who I want to know and who I don’t, and who I want to BE in those relationships. Made me realize I want fewer people around me, but safer people, and that I need to be making sure those few people feel seen and known by me, not just the other way around. I think we fuck that up in this culture, I know I have. I wasn’t there yet on the BILL album. As we spoke about, this record was met with some weird shit when it first came out. I lost even more friends, people were competitive and unsupportive, and it was hard to hold it all up. I didn’t do a great job of it. The grief album then became something to grieve. And now, Steve himself has died. And I just want to stand next to the record and hug it, hug Jerry and Steve and myself, and be proud of what we all made together. It takes so much courage to make work, especially honest work, and we all did that. Fuck what other people think about it. It belongs to us, and to me. I’m oddly grateful to have a new opportunity to do a better job of standing next to it right now. I’d give anything for Steve to still be here for it, but I’m doing what I can with what’s true.

HPFB: If you're comfortable revisiting, who exactly is Bill?

BA: You now, I’ve never actually spoken about it! I think maybe three people on earth know what the name means, who/what it references. When I first read your question, I was like, I can’t answer that! But maybe I can. It’s been a long time.

So, as I said, I lost some friendships before, during, and after the BILL album. Why did that happen? A few reasons. But the primary reason that more than one woman gave me, was the absence of my former softness. They liked me better when I was . . . more accommodating, more giving, and honestly, when I hated myself more. I’d had a reckoning with myself, with my own internalized misogyny, and my own contributions to the problems I was fighting in the world, and they didn’t like the new me. They flatly didn’t like my new confidence and boldness, and they said so. When I had that reckoning with myself, one of the things I came to terms with was the fact that I’d grown up listening to men talk about how much they hated women—and the delivery system they used was punk rock. I had digested misogyny and other weird belief systems my whole life and never questioned them! None of us did! So, I started talking to my friends about it, about how I was putting all that shit away, learning to be on the side of other women—shit, on my OWN side for a change. And my old friends didn’t like it.

Bill was someone I used to admire, used to want to make records with. He was in a band I would have told you was my favorite band a long time ago. And that band is fine, whatever. I’m sure they’re nice enough guys now; I’m sure they’ve cleaned up their shit. But for the bulk of their career, they weren’t on my side, or any woman’s side, really. And yet, I’d made them heroes, people to listen to. We all did. Until I didn’t. I named the record BILL because it was emblematic of what I was letting go of. Other people, other heroes, other dynamics that injured or disrespected me. I was learning to hold on to myself. Learning to be the hero of my own story. Learning to be enough. As I say in Resolution of the Wants, “You see, it wasn’t about you; it was about the bigger picture, the whole view.”

Meant it.

HPF: Anything else in the works or that you’d like to tell folks about?

BA: We’re touring later this summer and into the Fall, in support of our newest album MASS as well as BILL - The Steve Albini Mixes, and we’ll also be playing some brand-new work that hasn’t been recorded yet! Please check our dates and come hang if we’re anywhere near you!

I have some new solo music in the works, currently being mixed, and I’ll be sharing about that later in the year. Thanks for asking!

You can check out the re-release of BILL on Friendship Commanders’ Bandcamp, Spotify, and Apple Music. Find more good stuff right on their website.

Before I let you all get back to that cold, festering coffee you forgot about an hour ago, I wanted to share one recent video that Buick posted on her Instagram.

I was thankful that she posted this because it really resonated with me. One reason I started this blog was that I feel like even with some of my friends’ bands whom I might have seen live twenty times, at the end of the day I can't often tell you what a lot of their work is “about.” I've considered myself more of an instrumentalist than a songwriter in the past, so sometimes yes I'm just doing something because it's loud and fun. But if I do write something meaningful, I'd like to tell somebody about it at some point. Like she said, “Why was this important enough to write about?” When I asked Buick about this video she said that she feels that this phenomenon comes up more in certain cultural pockets than others, especially in heavy music where it’s “uncool” to talk about your own work. There’s an expectation sometimes that artists are just supposed to “release something, make a video post about it, [then] move on and act cool for the next ten years.”

BA: But you know, I don't make work like that. I make very earnest emotionally expressive music that's message-based. So for me, that's like a ridiculous move, but… you're sort of made fun of for talking about yourself or for needing any sort of space to take up. I do think that a lot of us sort of lapse into these roles of being like, “Hey guys, this is out. [Here’s] whoever made it, whoever recorded it, whoever mastered it. Like it or don't.” And I'm like… I would love to hear more about everyone's work. I honestly mean that. I'm curious about everybody's work. I was in [the studio] interviewing Steve about Song of The Minerals because he was like, “Well my lyrics are optional. I'm not a real songwriter.” I'm calling bullshit. I’ve been listening to the song my whole life. And he was like, “…Well, that song is about something.”

~RMSC